First NOMIS–ETH Fellow Dr. Craig Walton - first days at ETH

1 September 2023 is the starting date of the postdoctoral fellowship of the first NOMIS–ETH Fellow Dr. Craig Walton. As a fellow within the Centre for Origin and Prevalence of Life, Dr. Walton will closely interact with Prof. Maria Schönbächler from the Department of Earth Sciences, the host of Dr. Walton at ETH, as well as with many other members of the Centre and the members of their research groups. A warm welcome to Craig !

Following the announcement of the first NOMIS–ETH Fellow in April this year, Dr. Craig Walton officially started his fellowship with the Centre for Origin and Prevalence of Life at ETH on 1 September 2023. One of the first things on the ToDo-list was a visit to the new COPL spaces in the HIT building on the G-floor.

In the following, Craig shares his impressions and thoughts about his future activities with the Centre and his new colleagues from ETH.

The Centre for Origin and Prevalence of Life (COPL) is opening its new doors. Fellow ETH members, take note: the doors are now real, and they are open to you!

Having just arrived at ETH Zürich to begin a 4-year NOMIS–ETH research fellowship, touring the headquarters of COPL was both my first official duty and a complete pleasure – thanks to the wonderful COPL managing office, pictured in this article. COPL will be my first home intellectually and socially at ETH – and not just in an abstract sense! The centre is now a physical entity, with dedicated and quite beautiful space for offices, coffee meetings, seminars, and small group meetings laid out on the G-floor of the HIT building at Hönggerberg campus.

The COPL is designed to encourage interdisciplinary collaboration. Scientific events will always have a broad pitch, allowing everyone in attendance to engage fully with the topic of the day. At the same time, world experts will be speaking and attending on each occasion. This format, whilst accessible for all, therefore, still provides cutting edge insight and exciting discussion for attendees.

Similarly, the numerous spaces for smaller discussion groups can be freely booked. I am already making plans for invite fellow COPL members to the space to discuss collaborations and new ideas – perhaps over coffee, perhaps over lunch at one of the various campus restaurants. There are many possibilities, and lots of inspiration to be found.

Talking of inspiration, we are now in the process of fleshing out the COPL spaces with scientific, artistic, and functional materials. If you have an idea for a display piece or have anything relevant to the mission of COPL that you would like to contribute, please reach out to us! Our emails are listed at the end of this article, and we will be enthusiastic to reply. Already in motion are ideas to display geological samples of ancient rocks and meteorites, as well as large format scientific diagrams, charts, and data that reshaped our view of life, planet Earth, and the universe, backed with vistas of the insights that they have afforded.

Cellular structure. Genetic codes. Prebiotic chemical reactions. The swirling cloud decks of potentially habitable exoplanets. The possibilities are vast. Reach out with your ideas!

As I toured the COPL, the same conversation kept recurring. Are we alone in the universe… and what can we do to find out? This seems to be the question that is on everyone’s mind these days. It is a great question, and one that sits at the heart of COPL’s scientific mission. Whilst so much remains unknown (and, therefore, to be discovered!), I share here my thoughts on the matter. I look forward to hearing myriad other views at COPL over the coming months!

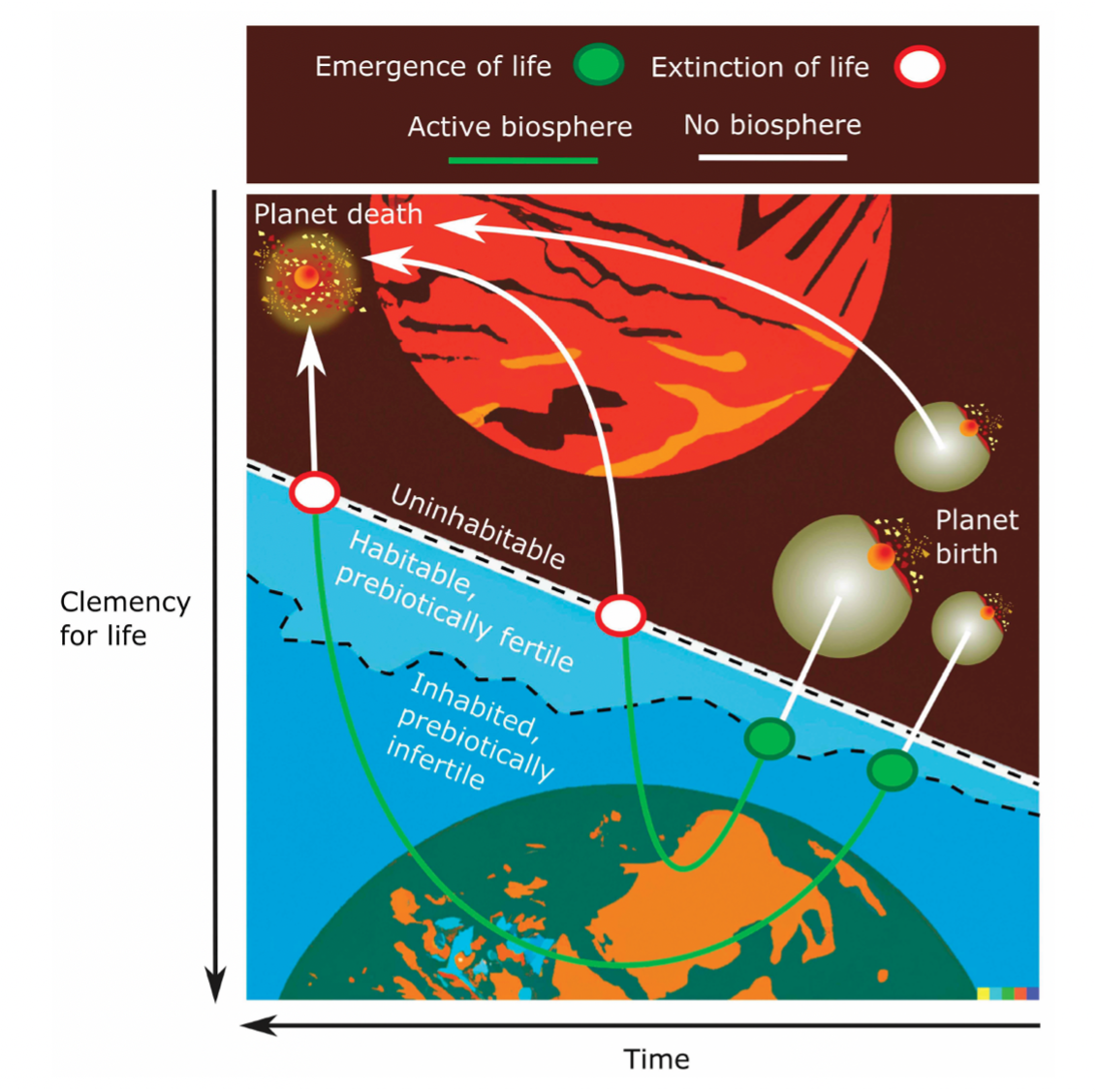

The first thing to stress is that the keys to answering the giant ‘Are We Alone?’ question are nicely listed in COPL’s own name. We need to figure out the likely Origin and the plausible Prevalence of Life in the universe. Given knowledge of the minimum conditions needed for life to begin, one can put numbers on how many exoplanets could ever possibly have given rise to a biosphere. Given the further knowledge of how long biospheres can survive on a given type of world (read: how often life is wiped out, whether by astrophysics, geology… or itself), we can then put crucial numbers on whether or not we are likely to:

- Have been alone, all along (no other life in last 4.5 billion years)

- Be alone, right now (no life currently, whether or not it existed before)

- Be forever alone, even into the future (no life other than Earth’s, in the future)

To gain this knowledge, we will therefore need to somehow constrain events to which we will never bear direct witness (Figure 1). We will never observe life emerging for the first time on another world (at least, naturally!), and we will never observe all life going extinct on another world I(and, we can hope, not on this one, either…). Given the geological sluggishness of nature, exoplanetary observations will provide us with a fantastical array of moments, but never individual stories (Figure 1). Every world that we observe will either be before or after a fundamental biotic transition (Figure 1), whereas on Earth we have rocks and fossils to trace out the whole history. Individual Instagram posts from different “planetary” accounts, versus Earth’s storied Facebook timeline, in other words.

The central relevance of Earth, as our sole example of how inhabited worlds change over time, will therefore remain even as we expand our frontiers of knowledge using astrophysics and lab experiments to observe and predict the distribution of life in the universe – as determined by its frequency of first emergence, and probability of total extinction…

Compounding the problem is the fact that every Earth-like world will in fact be somewhat unique, with the same probably going for any native alien lifeforms. Moreover, even a re-run of Earth history is unlikely to reproduce the same end result (e.g., no humans, or perhaps simply no Facebook). Indeed, the non-linearity of planetary evolution even given similar initial conditions stands as a shadow across all attempts to describe the Prevalence of life. Only with immense scientific rigour and attention will we satisfactorily encompass the possibilities, and in doing so properly adjust our lenses to bring life in the Universe into focus.

“The quest starts now, with COPL. So, come along and be part of it, and help us shape the questions we focus on! Together, we might just find out some of the answers.”Dr. Craig Walton

Of course, what exoplanet observations may well reveal is a definitive detection of life present right now on a different world. That would put to rest the question of ‘Are We Alone?’ and, in a strange sort of circularity, refocus us once more on fundamental broad questions about the Origin and Prevalence of life in the Universe. So really, whatever we find, we won’t get away from those issues, which sit at the heart of an entire emerging field of interdisciplinary science.

The quest starts now, with COPL. So, come along and be part of it, and help us shape the questions we focus on! Together, we might just find out some of the answers.